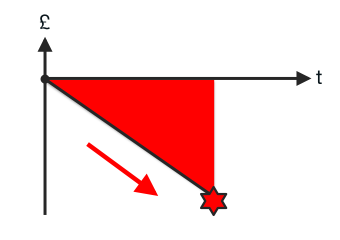

Fundamentally, a transformation is a learning process – empirical and experiential. Making change upon change can get us lost in space, not knowing which way is up or down, left or right. Measurement is the only way to retain a handle on what’s real. Plan, do, check, act. Design a way to measure the impacts of change in terms of the desired results.

How can we know what to change?

Every company operates according to its policies. Those policies are encoded into the processes. Some policies are good – they make sense; some processes are effective and efficient enough. Some policies and processes are not so good. How can we know which ones to change? Do we go after the easiest ones? Or the cheapest ones? Or the ones people complain about the most? Perhaps we should just start again?

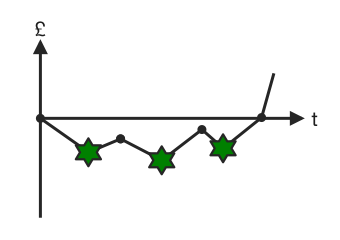

In knowledge working the constraints can be invisible. What we see is the tip of the iceberg. The bulk of the ‘berg, hidden beneath the surface, is really dictating what happens. It’s easy to assume, knowingly or not, that we work within an ordered system. “Danger Will Robinson!” Beware the retrospective coherence trap. For example, doing Scrum will not necessarily lead to the desired results. The world of software development and delivery is complex. How can we identify the weakest link in an invisible chain? Our approach to change needs to be scientific. Let’s collect hard data and analyze it, and verbalize our intuition and emotions as we rigorously test our assumptions. Then we can better understand the system and select where to intervene and make changes that will lead to improvements.

Change to what?

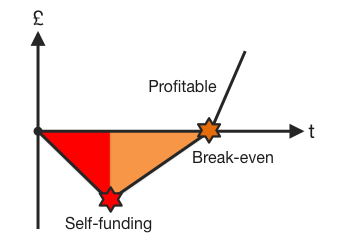

When we find a bonafide constraint what do we replace it with? What will the improved system look like? How will it feel? How will it behave? We’ve all experienced solutions that didn’t work, solutions looking for problems, and solutions that fixed the problem but also caused other problems. What does better look like? How will we know when we get there?

There’s a need to clearly show how the selected action leads to the elimination of the constraint; how the proposed solution solves the defined problem. Describe the desired future in a way that we can determine what we want, why we want it, and avoid unintended and undesired consequences that might result. And let’s measure the outcome (and impacts) of each change.

How to cause the change?

It’s easy to spend a lot of our time doing stuff. Then we get frustrated because we’re working so hard, doing so much, and improvement just isn’t happening. Our busy-ness isn’t taking care of business. We come up with solutions fast – arguably before we truly understand the problem. As Einstein said:

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

Let’s take the time to work through why we think a specific action will lead to a specific result. Moreover, it seems like we rarely stop to define, in a quantifiable way, the outcome we’re trying to achieve. By unambiguously defining problems or constraints, and the desired outcomes, we can systematically design and execute the steps to overcome the obstacles in between and recognise when our plan should be altered.

Stop and think. Then do

In an age where agility has quickly become the key to competitiveness, the demand for a change blueprint wrapped up in what’s being called an Agile Transformation is about as bogus as it gets. Business agility and true competitive edge lie in our ability to learn faster and generate deeper knowledge and to use that knowledge to inform purposeful action – deliberate and designed actions that solve clearly defined problems and produce unambiguous and valuable business outcomes.